Was My Mother Right?

Navigating Rape Culture

Marie: We all have that voice in our head, that critical voice, it’s our mother’s, or it’s more abstract. It’s a voice that says, “I knew it! You shouldn’t have done that/gone there/worn that dress….”

If you’ve experienced violent, forced, physical attention, that voice can condemn you and throw you into a pit of self-doubt. ‘Was I asking for it?’ ‘Was I provocative?’ ‘Did he really rape me, or do I sorely regret the sex we had last night?’ and add to that ‘I can’t even really remember.”

Response to trauma is complex and we are not in control of it.

It’s Rare We Report

Given the common responses to reporting assault, it is statistically rare that someone lies about being raped. In fact, it is much easier for victims to engage in self-blame than to face the disturbing fact that they had no control over what happened even when violated.

Add to that, ‘I am black/Latina/lesbian/transgender… and no one will believe me.’

Alternatively, ‘I’m a man. This never happens to men.’

Given the common responses to reporting assault, it is statistically rare that someone lies about being raped. In fact, it is much easier for victims to engage in self-blame than to face the disturbing fact that they had no control over what happened when violated.

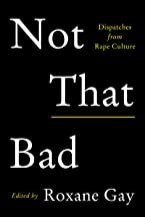

Janet: What Roxane Gay, the author of “Not That Bad, Dispatches from Rape Culture” asks “What is it like to live in a culture where it often seems like it is a question of when, not if, a woman will encounter some kind of sexual violence? What is it like for men to navigate this culture?”

On a day off from writing I watched a new movie titled The Last Duel, available on Netflix. It stars one of my favorite actors, Jodi Cromer, so I watched. The action takes place in France and is immortalized in paintings and stories of that era, the 14th Century. The law about reporting rape, at lest in the noble classes, is written in the script that if the wife of a lord is raped and she reports it, the resolution is up to God. That required a jousting duel on horseback. The combatants, the husband of the accuser and the accused, are in a fight to the death. If the husband wins, the couple is free. If the accused wins, the wife is burned at the stake, on the spot.

In this movie the wife speaks:

“The penalty for bearing false witness is that you are to be burned alive,” an official tells Marguerite in the movie. “I will not be silent,” she responds, teary-eyed but defiant.

It’s a bloodthirsty movie and I’m no critic, but good or not, it made a point.

Through centuries women have been blamed for causing rape, accused of being seductive witches, or worse. When I asked a preacher/minister questions about the prospect of divorcing my abusive spouse, I was told it was my duty to take the abuse (men will be men), quiet my temper, my voice, and keep my family together.

I didn’t talk about my rape in high school for reasons of survival. Not worried about being burned at the stake, but what could happen if I did tell? From my book “Survival Isn’t Mandatory” the reasons I didn’t tell my parents are in the form of a letter written in my diary, that summer of 1964.

Dear Mom,

I’m sorry I didn’t tell you, and I never will. I’d known since I was nine that I reflected your success as a mother. I could not bear to witness your imagined failure. I was too weak to fight; I was blind and ashamed to let myself get into that room. I thought I was strong, but I couldn’t…didn’t fight back.

I didn’t tell dad. He might drive through town with a shotgun and cause a problem bigger than mine.

Mom, I filled the hollow space with silence and locked the top. I added a bow to disguise it. I prayed the thing could never escape. It struggled to get out, and after a while, it quieted down, withered, and slept.

I love you, mom, and always will.

The sad part is that “thing” was the source of my life choices, and though my success and strength are the product of defiance, I have the will to live.

What Marie says is true, “These are the voices of rape culture. Together, we must amend this voice.'“

Closing the introduction in her book, Roxane writes,

“This is a moment that will, hopefully, become a movement.”

We have one. It’s called Our Silent Voice a Book, a Movement, a Stand.

Join us, we who report, who talk about it, and break the silence.